How ADHD Medications Work: Demystifying ADD

| Dan Bolton 11/15/2012 |

The diagnosis and treatment of ADD has had a controversial history. The medical establishment has identified ADD as a diagnosable disorder and outlined specific treatments to mange symptoms. However, some groups have claimed that ADD is a conspiracy developed by the pharmaceutical companies to make money off the sales of drugs developed for what they deem a fictional disorder. Given this history, it seemed appropriate to address the issue of ADD and the efficacy of medications in this week’s blog.

To clarify, Attention Deficit Disorder, or ADD, is a diagnosis for those with symptoms of inattention and difficulty sustaining concentration without more overt symptoms of hyperactivity. ADHD stands for Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder, which is similar to ADD, but symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity accompany symptoms of inattention. ADHD can be used to identify people who have problems with impulsivity alone, but can also manifest in a combined type, in which problems with sustaining attention and hyperactivity are both present. The use of ADD in this article encompasses broad range of aspects of both disorders: short attention span, distractibility, disorganization, poor impulse control, poor judgement, and difficulty learning from past mistakes.

When I first began work as a therapist I personally was adverse to the idea of using medications for children. In fact, I believed the hype that ADD was not a real disorder. I thought the bio-psychological concept of ADD was oversimplified and could better be explained as a more complex outcome of various environmental disturbances in the early development of the child.

Working as a therapist over the past 8 years in school settings, my perspective on ADD has shifted dramatically. Between hours of both direct counseling and classroom observation, what has struck me most is the effectiveness of medications in helping children diagnosed with ADD to function in the classroom. This experience has convinced me that in the nature vs. nurture debate ADD does in fact fall on the nature side, and is in fact hereditary. The environmental influences on ADD are important though with emphasis on how the people in the child’s life react to and handle the challenges this condition brings.

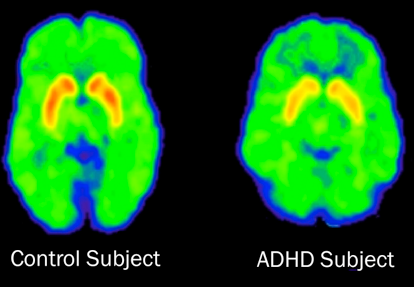

Outside of what I have witnessed in children’s behavior, what has convinced me even more is the new extensive documentation of brain activity that can be observed directly via neuro-imaging. There are a few different types of neuro-imaging technologies, one being the more traditional functional brain MRI (the image below), and newer imaging known as SPECT, used and demonstrated by Daniel Amen, M.D. in the book Change Your Brain Change Your Life. The differences in brain activity between the image of a brain of a person with ADD as compared to a person without ADD are undeniable. As you can see in the image below the “ADHD Subject” has a significant and observable difference in the both the front part as well as the mid to rear part of the brain than the “Control Subject.” The “ADHD Subject” shows deficits in the part of the brain called the Prefrontal Cortex, which is the area of the brain responsible for sustaining concentration, planning, making decisions, and moderating correct social behavior. The difference in functioning of the Prefrontal Cortex is highlighted by the blue areas at the top of the picture, which signifies low activity. Also notable is the higher activity level in the mid to rear part of the brain of the “ADHD Subject”, which is the limbic system known as the emotional center of the brain. Both the lower activity level in the Prefrontal Cortex and higher Limbic activity can account for the ADD/ADHD person’s impulsivity, quickness to anger and other trouble regulating emotions and excitement leading to overstimulation.

When the brain of a person with ADD is not medicated, the functioning of the Prefrontal Cortex is compromised. This leads to the following two outcomes that can be seen in the brain image above:

- The person’s Prefrontal Cortex is under-active. When under-active, the person with ADD has trouble sustaining focus and the PFC resorts to seeking excitement and stimulation.

- The PFC is not able to serve its function to inhibit signals from other parts of the brain, such as the limbic system. When the Prefrontal Cortex is not working to send inhibitory signals to the limbic centers of the brain, the person with ADD/ADHD can be overwhelmed by emotions or other sensory signals from other parts of the brain as well. This can lead to the sense of overstimulation often reported by people with ADD/ADHD.

OK, but let’s get back to the question: How in the world would giving a stimulant medication help an already over-stimulated person to be more calm and more focused?

It seems counterintuitive that an overstimulated person seeks out more stimulation. However, it is the relative lack of activity and stimulation in the Prefrontal Cortex that craves more activity. Read that again, yes, MORE ACTIVITY! The person with ADD is overstimulated, yes, BUT, this is because their Prefrontal Cortex is UNDER-STIMULATED. To compensate for the under-activity in the Prefrontal Cortex, the person with ADD seeks stimulation. For example, if the person is in a classroom and expected to sit quietly and concentrate, they are likely going to become restless. This is why parents question the diagnosis of ADHD making statements like: “He can focus when he wants to. He can play video games for hours without breaking concentration.” This is true for kids with ADD because the video game is providing them the high level of stimulation their Prefrontal Cortex is seeking. Similarly, people with ADD also typically engage in high risk and even obnoxious behaviors because it provides that dose of stimulation their brain is seeking. At school kids with ADD may turn on this part of their brain by provoking conflict, causing disruptions in the classroom or even seeking fights. This charges up the emotional centers of the brain, which in turn feeds the Prefrontal Cortex that is lacking stimulation, and helps them feel more tuned in. When stimulation cannot be found from the outside, worrying, focusing on problems, anger, and other negative emotion can be used by a person with ADD as a maladaptive form of self-stimulation. This latter finding of conflict seeking behavior is a more recent insight developed directly from SPECT images of Dr. Amen’s clinics.

ADD medications work because they provide the stimulation, internally, to the Prefrontal Cortex by correcting the brain chemistry with a concentrated increase of neurotransmitters it is lacking. They do so by helping the brain deliver a concentrated increase of dopamine and norepinephrine to the Prefrontal Cortex (Craig Berridge from the journal Biological Psychiatry) so that this part of the brain can serve it’s proper function. This in turn helps the person with ADD/ADD not need to find stimulation through seeking excitement, causing conflict, or getting charged up by his or her own negative emotions.